Foot and Lower Leg Ulcers

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Venous stasis ulcers, arterial insufficiency ulcers, and neuropathic ulcers are the most common ulcerations of the feet and lower extremities. The proper diagnosis is important since treatments are directed at the underlying cause.

Venous Stasis Ulcers

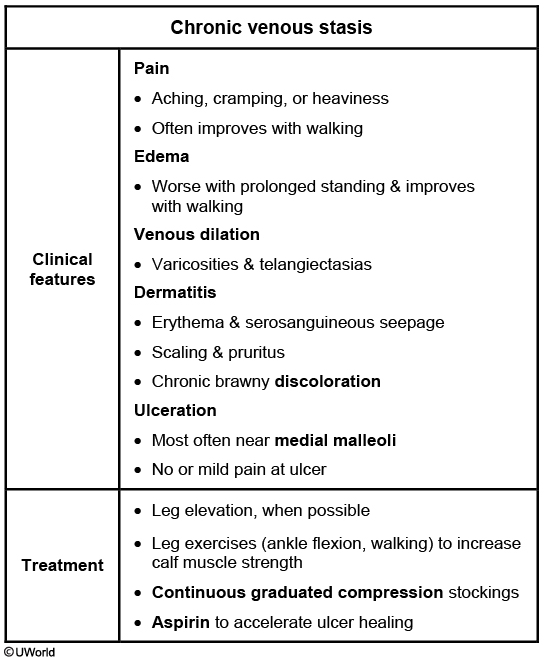

Venous stasis ulcers account for up to 70% of all leg ulcers. They occur on the lower extremities in the area from the midcalf to the ankle, most commonly near the medial malleolus, and are associated with signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Venous stasis ulcers can be single or multiple and are typically irregularly shaped, shallow, and often weep serous fluid (Figure 157). The presence of fibrinous tissue is common, and ulcers are rarely necrotic. Pain may or may not be present.

Venous stasis ulcers of the medial lower extremity with associated changes of edema, hyperpigmentation, and evidence of previous healed ulcers.

Venous stasis ulcers of the medial lower extremity with associated changes of edema, hyperpigmentation, and evidence of previous healed ulcers.

Physical findings suggestive of venous stasis ulcers include edema, varicosities, eczematous changes, brown pigmentation from hemosiderin deposition, lipodermatosclerosis (fibrosis of subcutaneous tissue), atrophie blanche (pale plaques of scar tissue), and evidence of healed ulcers. Diagnosis is usually made clinically, although duplex ultrasonography can be helpful in evaluating venous reflux and obstruction, or if the diagnosis is unclear. Ankle-brachial indexes should be measured to rule out concurrent arterial disease.

Treatment consists of compression therapy, which improves venous flow, reduces edema, and promotes fibrinolysis. Compression therapy is best administered through the use of high-compression, multicomponent bandaging; other options include elastic or inelastic compression bandages (Unna boots, compression stockings) or intermittent pneumonic compression devices. Compression is avoided if the ankle-brachial index is less than 0.8, and referral to a vascular specialist should be considered.

Local wound care includes debridement of devitalized tissue. Simple nonadherent dressings appear to be as effective as other more expensive dressings, and the addition of topical cadexomer iodine may improve healing. When added to standard care, oral pentoxifylline, simvastatin, and aspirin have been shown to increase ulcer healing. Lower quality evidence suggests that flavonoids and hydroxyethyl rutoside may also improve healing. Routine use of systemic antibiotics is not recommended except for patients with suspected infection (increased pain, drainage, surrounding cellulitis). Superficial venous surgery reduces 1-year ulcer recurrence rate in patients with superficial venous reflux. Bilayer artificial skin replacement may improve healing of venous ulcers compared to compression and simple dressings.

Supplementation with oral zinc sulfate has been proposed for the treatment of arterial and venous lower-extremity ulcers, but trials to date have found no significant beneficial effect.

Arterial Insufficiency Ulcers

Arterial leg ulcers account for up to 25% of leg ulcers. Arterial insufficiency is typically due to atherosclerosis, which leads to inadequate oxygenation of the tissue and ulcer formation. Common risk factors are smoking, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and increased age. Common locations are the distal toes, on the anterior portion of the lower leg where minimal collateral arterial circulation is present, and at sites of trauma. Arterial ulcers are usually painful and have sharply demarcated borders with a dry, pale gray or yellow wound base without evidence of granulation tissue (Figure 158). Claudication and rest pain are commonly present. If tissue necrosis is present, the wound may be covered by an eschar. Other findings include cool extremities with digital hair loss; shiny, taunt skin around the ulcer; and delayed capillary refill time. The key diagnostic test is an ankle-brachial index less than or equal to 0.9.

Arterial insufficiency ulcers appear sharply demarcated or “punched out” with a dry pale, gray or yellow base and the surrounding skin is red, taunt, and tender.

Arterial insufficiency ulcers appear sharply demarcated or “punched out” with a dry pale, gray or yellow base and the surrounding skin is red, taunt, and tender.

Treatment must involve aggressive risk factor management and measures to increase blood supply to the affected area. Surgical revascularization, percutaneous balloon angioplasty, or stent placement is usually necessary. Arterial ulcers are treated with local wound care similar to venous stasis ulcers.

Neuropathic Ulcers

Neuropathic ulcers arise secondary to repetitive trauma to the skin, typically in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and a reduced awareness of pressure or trauma to the skin. Diabetic ulcers are painless, are most common on the plantar surface of the feet, and have associated callus and foot deformity (Charcot foot) (Figure 159). The skin is warm and dry with signs of fissuring and breakdown. Polymicrobial infections are common, and patients are at increased risk of osteomyelitis (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease). Surgical debridement of necrotic tissue along with redistributing pressure is important to achieve healing. Offloading measures include foot inserts, therapeutic shoes, and removable cast walkers.

Neuropathic ulcer located over the first metatarsal head with associated callus in a patient with diabetes mellitus.

Neuropathic ulcer located over the first metatarsal head with associated callus in a patient with diabetes mellitus.

Other Causes of Lower Extremity Ulcers

Pressure ulcers of the heels and lateral ankles are common in bedridden patients due to necrosis from persistent pressure. Rarer causes of ulcers (Table 35) should be suspected based on a suggestive history, physical findings, and lack of response to traditional therapies. In these cases, a punch or incisional biopsy should be considered. The sampled tissue should include both ulcer edge and bed, and the tissue should also be sent for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Further workup and treatment are directed at the underlying cause.